Any casual observer of the world’s state of affairs knows that advanced economies have been in trouble and emerging markets and China in particular have been important drivers of global economic growth. Despite concerns of “emerging market turmoil” over the last couple months, there has been a sense of unease and fear in advanced economies that the rise of emerging markets will threaten their way of life and economic well being.

Yes, the rest of the world is rising. Yes, advanced economies are still advanced.

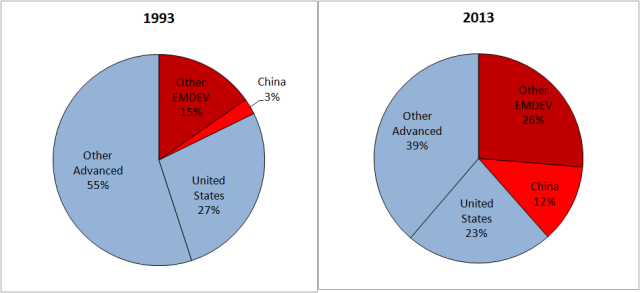

Since the early 1990s, China’s share of total world income jumped from around 3 percent to around 12 percent to become the second largest economy in the world. Despite the fact that all other emerging and developing (EMDEV) economies in the world combined are only twice as large as China alone (and increased their share of global GDP by roughly the same amount as China over the same twenty year period), China by itself still contributes about as much to global income growth as that whole group.

Though advanced economies have lost over 20 percent of their share in world income and are growing at about two percentage points lower than the non-China EMDEV group, they still contribute to world growth about as much as that same group over the last two years. This shows how both the rest of the developing world as a group and the advanced economies are just as important as each other for global growth – a relatively new and key aspect of the 21st century global economy.

Contributions to World GDP Growth

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2013 and January 2014 Update

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2013 and January 2014 Update

Aside from the importance of China and EMDEV to global growth, the chart above reveals two important characteristics about the world economy and its structure. The first is that global growth is returning to the rates it had seen over the 1990s, and the second is that that growth is occurring more rapidly in EMDEV than in the advanced economies who had previously accounted for over 80 percent of total world growth over the 1990s.

A careful analysis of this second characteristic shows that the story of today’s world economy is not one of advanced economies losing out to EMDEV economies, but one of EMDEV economies catching up and converging with the high standards of living already achieved in advanced economies. This story of convergence does not imply that a shift in wealth from one part of the world to another is taking place. Convergence implies that one part of the world’s wealth is catching up to the other part’s, moving the world towards a more balanced distribution of global income that better reflects the distribution of the world’s population. The rest of the world as a group is indeed rising, and advanced economies are indeed still advanced. As a matter of fact, despite lost global income share and relatively slow growth rates, advanced economies still account for over half of world income with only about 14 percent of the world’s population.

The drivers of catch-up growth are dependent on an economy’s ability to absorb technologies through international trade and financial linkages, to translate productive investments into economic opportunities, to educate its population and most crucially to strengthen its institutions. Kemal Derviş provides an excellent overview of convergence, interdependence, and divergence in the world economy.

Despite China being the second largest economy in the world, its population of over 1.3 billion people leaves its GDP per capita (income per person) of $9,800 (PPP) at 92nd in the world, behind countries like Brazil, Turkey and Mexico, who themselves still face a long road of economic, political, and social development. Income per capita of about $41,520 (PPP) on average in the advanced economies is what these fast growing emerging markets and the Chinese are after. So, although the shares of global income for advanced economies are decreasing (it is worthwhile to note that over the last twenty years, the United States’ share of world income has only declined by around 4 percentage points, while that of other advanced economies has shrunk by over 16), the global balance of wealth on a per capita basis is still highly skewed.

It is important to note, however, that although the rates of income inequality between countries are reversing and beginning to narrow, rates of income inequality within countries are increasing for both advanced and emerging market economies alike. This is another phenomenon that deserves a lot of attention because its implications and consequences are far reaching. Certainly a topic worthy of attention, as discussed by several leading policymakers and experts and as researched by the IMF.

Note: Countries included in “advanced” and “emerging and developing” groups are based on the IMF’s classification, shown here. All data from IMF World Economic Outlook October 2013 and January 2014 Update, except for world population from U.S. Census Bureau.

Shares of World GDP (market prices) Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2013

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, October 2013